A Feast for the Eyes

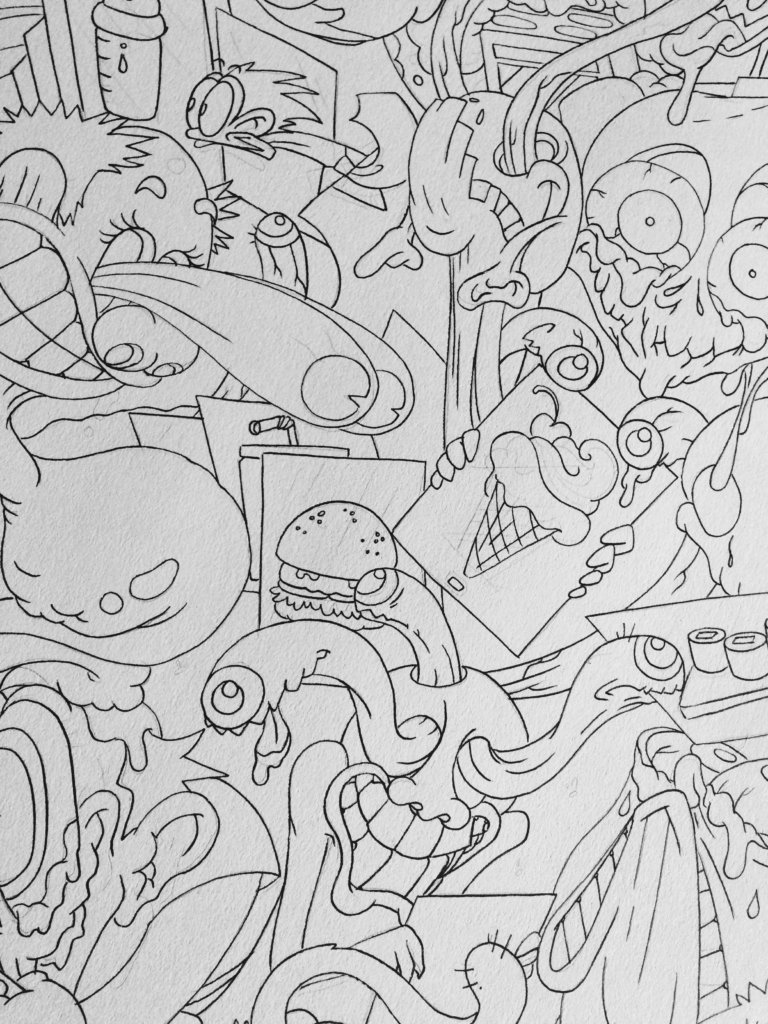

“A Feast for the Eyes” is a 75cm x 55cm illustration that uses black and white ink with dip pens on 80lb., grey, deckle-edge Strathmore paper. It is a large, confronting piece rendered in the art style of early cartoons from the 1920s -1930s called “Rubber Hose.” The name and style refers to the bendy, tubular limbs of cartoon characters made famous by Disney and Fleischer Studios during the early twentieth century, such as Felix the Cat, Betty Boop and Steamboat Willie (who later became Mickey Mouse). It is a style that draws its inspiration from surrealism and abstraction, that coupled with the characters’ extravagant use of knives, explosives, and poisons to combat their antagonists, is a style that tends to evoke humour as much as perturbation in its audiences.

The piece uses a surreal art style to reflect a surreal theme. Generally speaking, “A Feast for the Eyes” reflects the messy ecology that comprises today’s image-hungry consumer culture and distorts it further through speculation. This is a broad arena to play in, however I have focused on an aspect of consumer culture that is obsessed with the imagery of food; driven as it is by the glamourized visual (and audial) appeal of food as projected through the lenses of social media and television. Sometimes coined as “food porn”, these are images and footage of food made to be so sensually attractive—while disallowing touch, taste, or smell—to arouse a similar desire and appetite that real food would otherwise elicit. In many ways, these images are designed to stimulate both literal hunger, and a hunger for the things these images symbolize or represent, like exoticism, wealth, or possibility. They aim to fuel a certain vicarious living while simultaneously stirring audiences with frustration at the inedibility of their subject. I find this a particularly intriguing and unsettling phenomenon. It is an engagement obsessed with the material qualities of food… without the material qualities of food.

In his book In Defence of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto (2008), author Michael Pollan echoes this phenomenon with what he calls “The Cooking Paradox.” Here Pollan reflects on what it means for our social fabrics as the practices of cooking and commensality jostle for dominance against the tweet-and-share of digital food, and spending more time eating with humans onscreen than with ones in the flesh. But of course, pixel-food could never realistically replace its material counterpart—could it? What if it did? Musing on the writings of Pollan and other scholars debating the fate of a world where the realities of cooking are increasingly staged amid the artifice of television and social media, through “A Feast for the Eyes”, I speculated what the world might be like if, so engrossed with digital food, we forgot to eat. We forgot to cook. We moved deeper and deeper into a life online and onscreen, and left behind our responsibilities as mortal, physical animals. I had read somewhere about evolutionary theorists speculating the physiological development of the human body as the internet and its offspring of digital devices became increasingly necessary tools for our daily existence. Some had suggested the aggressive growth of the human eye and its adaptation to low and blue light. Others speculated the atrophy of some fingers, yet perhaps the growth of another thumb. Hunchbacks. Crooked necks. Grim, but inspirational stuff. What else did a life increasingly online mean for the human body and its material environment?

I started the work by imagining how a life that prioritizes visual consumption over the literal ingestion of food would transform the human body. Therefore, the figures you see in the piece bear vague resemblance to human animals in various stages of decay; their bodies adapting to the consumption of sound and pictures instead of macronutrients. Body parts litter the chunk of earth at the base of the image as they melt from their hosts. At the same time, eyes have taken on lives of their own and feature everywhere, devouring images of food that fuel their growth, but do nothing to sustain the rest of their bodies. While I played liberally with the concept of physical decay, I asked what else would start to decompose, or become forgotten without our desire to cook or eat real food. Would someone remember to feed the dog? Would we invest time or money in kitchens, ovens, or dining tables? Would the responsibilities of the material world recede to the background of our consciousness as we become further engrossed in our virtual realities? In his book Ready Player One (2011), Ernest Cline does a skilful job imagining such a dystopia where our material world becomes an unliveable place, yet with the right AR headset, virtual reality is an easy and satisfying retreat. Yet, like Cline, I made the piece as a commentary on the impossibility of forsaking the material world for the stuff of dreams: the meat of bodies still decays, the Earth still gets hotter, children still need feeding, and the cracks in the veneer keep expanding while the images become increasingly attractive.

Cline, Ernest. Ready Player One. Broadway Books, 2011.

Pollan, Michael. In defense of food: An eater’s manifesto. Penguin, 2008.